The English Convent

The English Convent

The domain of the English Convent in the Carmersstraat has been inhabited almost continuously by the Canonesses of Windesheim for almost four centuries. The monastery is a well-preserved and completely walled complex with a unique domed church and a spacious nineteenth-century landscape garden. In the English Convent lives a community of canons who have always devoted themselves to the education of girls (they keep a boarding school open from the start where they train English Catholic girls) and to hospitality. Priest-poet Guido Gezelle (1830-1899) was for a time rector of the English Convent and teacher at the boarding school. Thomas More (there is a relic of his in the church) and Geert Grote (Modern Devotion) are very important in the sisters' spirituality.

On February 26, 1628, the English Marie Lovell bought a walled property with orchard and house (the former fitting house Nazareth) in the Carmersstraat. A little later, the domain came into the hands of the English canons of the Order of Saint Augustine (Windesheim Congregation), who had been staying in Leuven for several years but were looking for a new place of residence closer to England.

It was not until 1647 that the community had sufficient resources to construct its own monastery building into which the former passers-by house Nazareth was integrated. The sisters had a monastery building, refectory, kitchen, common room and sleeping cells constructed. The first chapel was completed in 1650, but a century later, in 1736, a large church with a cupola was commissioned. This choice was defended as "the ideal model church to make weak sister voices sound better". The assignment was entrusted to the versatile Bruges architect Hendrik Pulinx (1698-1781). The richly upholstered domed church in classicist architecture is unique to Bruges. Prioress Lucie Herbert also had a large cloister built.

From 1766 Mary More, direct descendant of Thomas More, is the new prioress. She succeeds in guiding the monastery through the French Revolution. In 1794 the sisters fled to England, except for two sisters who guard the buildings and later buy them back. In 1802, all sisters can live in the monastery again. Because the sisters had returned from England, the population called the monastery 'English Convent' from then on.

In 1843 it was rebuilt again: Prioress Elisabeth Latham had the boarding house greatly expanded. In that period Guido Gezelle was spiritual director of the sisters and teacher at the boarding school. He lived in a house near the monastery and died there in 1899.

The first Belgian prioress was Marie Stanislas Liefmans, a daughter of the famous brewing family from Oudenaarde. She also expanded the monastery.

The sisters dropped out of boarding school in 1973 and, shortly after the turn of the century, they stopped taking in guests in the guest quarter.

The 'English Convent' is the only English Catholic monastery that, except for the French Revolution, has functioned continuously and still exists.

Priory of the Discalsed Carmelites

Priory of the Discalsed Carmelites

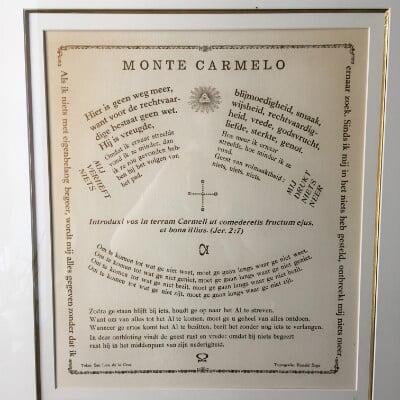

The Carmelites have been present in Bruges since the thirteenth century: the (‘calsed’) Carmelites had a monastery on the Carmersstraat. But under the impulse of the Spanish Teresa of Avila (1515-1582) the Reformed order of the Discalced Carmelites came into being and it is John of the Cross, a mystic and religious poet, who proposes to wear no longer shoes as a sign of a stricter monastic life. In 1593 the Discalced Carmelites became an independent order and foundations followed in the (Spanish) Southern Netherlands as early as the beginning of the seventeenth century. In Bruges, the female order was founded in 1626 and the male order in 1630.

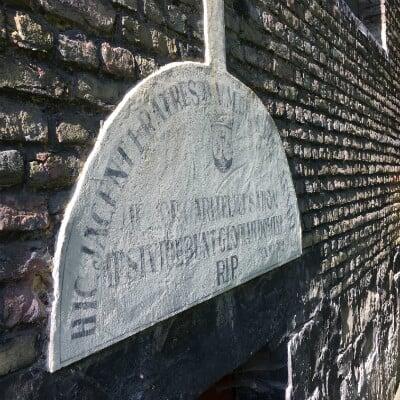

In 1633 the Discalced Carmelites moved into a building in the Ezelstraat. The court of Uytkerke, which dates from the fifteenth century, is still integrated into the current monastery. The ‘discalses’ (or unshod) bought several adjacent properties and initially renovated the existing buildings. In 1667 they built a new kitchen, hospital and cells, a year later a brewery and in 1686 a new ermitage, at the back of the garden. An intensive building campaign followed between 1688 and 1691: the church with an extensive choir, a library and part of the large building. The refectory and guest rooms were not built until 1723. In 1726 the second and largest part of the building was built.

The monastic community flourished in the eighteenth century: in 1773 it had forty members. In the French Revolution the monastery was closed and the priests expelled. The church and the monastery were put up for sale, but with the help of a banker the Ghent prior was able to buy the whole back so that the monastery could restart in 1802.

The Carmelite monastery is known for the large church, the spacious monastery building and the characteristic refectory in simple architecture, the imposing monastery library and the extensive garden with an ermitage and a seventeenth-century plague house.

Comprehensive Heritage Value

The Engels Convent and the Carmelite Priory are large monastic domains, both located in the historic center of Bruges and inextricably linked to the history and development of the city of Bruges and to the history and development of religious life.

Both monasteries are extraordinary sites with a particularly high heritage value that is all-encompassing.

“Both monasteries are extraordinary sites with a particularly high heritage value that is all-encompassing.”

“Both monasteries are extraordinary sites with a particularly high heritage value that is all-encompassing.”

The heritage value of the monastic buildings, associated buildings and large monastic gardens can hardly be overestimated. The buildings are protected. The gardens – each one a hectare in size – are oases of tranquility in the city. The heritage value of the movableproperty is also indisputable: the furniture, utensils and art objects bear witness to the history of the monasteries and their inhabitants and they also illustrate the craftsmanship, talents and inspiration of the craftsmen and artists who built and created them.

Moreover, both monasteries have valuable libraries and archives. The English Convent has a beautiful library and keeps interesting chronicles and manuscripts (including those of Guido Gezelle, Albrecht Rodenbach and Hugo Verriest) in the archive. The Priory of the Discalced Carmelites has an intact monastery library with over fifty thousand books and some valuable cradle prints.

But 'Sacred Books | Secret Libraries' also and especially focuses on the spiritual heritage value of the sites: the spiritualities, the way of life of the religious, their customs and the rituals of the monasteries form the starting point for the project. ‘Sacred Books | Secret Libraries' therefore goes beyond material and intangible heritage: this project unlocks spiritual heritage.